Media Contact

Email: [email protected]

A series of storms in February dumped heavy rain on parts of central and southern U.S., causing damaging floods along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

“Roughly 70 rivers were in flood stage as of midday Monday in the central USA, the National Weather Service said. Overall, more than 250 river gauges reported levels above flood stage from the Great Lakes to Texas,” according to USA Today (2/26/18).

These recent floods are a timely reminder that flooding can happen at any time. Floodproofing a structure with flood barriers, flood doors, flood logs or other mitigation solutions is important, but not enough to ensure protection when a flood hits (read more about common sense flood prep). A flood emergency operational plan is highly recommended for all floodproofed buildings, and may even be required in some communities.

Flood emergency operational plans include information about floodproofing measures during and after floods. For example, equipment that requires electricity, such as a sump pump, needs to maintain power through the flood event. The plan outlines how often to practice for a flood, who is responsible for the plan, and any underlying assumptions.

The plan should do the following:

In addition, an inspection and maintenance plan should be in place for all flood-protected enclosures and areas. At a minimum, this plan should inspect:

With more rain in the forecast and a nor’easter predicted for the East Coast, now is the time to review flood emergency operational, inspection and maintenance plans. For more information on flood mitigation planning, visit www.floodpanel.com.

Over the past few decades, more and more cities are recognizing — and acting on — the effects of run-off. The problem is a relatively new one, and is the result of rampant and poorly planned paving that has taken place over the last century. Before the advent of the automobile, there was very little problem with run-off. Dirt roads were the norm, and virtually all homes and businesses were surrounded by earth — not the cement patios, driveways, roads, sidewalks, and parking lots that have proliferated since the coming of the car. In this bygone era, even in the event of a major storm there was always plenty of natural, porous surfaces to soak up the water. Today, there is precious little ground left to absorb precipitation — most of it runs off to create devastating amounts of water in storm drains, rivers, and causeways.

The result of this type of wide-scale run-off can be deadly. Last fall, a major flood in northern Kentucky caused significant damage to homes, trailer parks, and businesses, and left at least one person still missing. The flood was determined to have been caused by unchecked run-off that simply had nowhere to go, even though the area is surrounded by a web of small streams and rivers that can absorb huge amounts of water. The effect of run-off water streaming from every paved surface is simply too much for even a vast system of waterways to channel safely.

Many municipalities have begun to take the threat of run-off very seriously. In San Diego, the problem was deemed to be so dire that the city sent out officials to visit businesses, schools, rec centers and commercial buildings to educate citizens about the need for conserving green spaces and the wisdom of creating new paved surfaces very sparingly. In that region of little precipitation, canyons act as storm control channels, and any buildings or homes located in the path of these canyons are in deep trouble during times of sustained rains.

In the state of Maryland, a special tax has been proposed to create a financial incentive to avoid the addition of new paved areas. The tax would be based on the square footage of pavement, rooftop, or other hard surfaces at each residence or business. The situation behind this type of tax reflects a predicament common to many municipal areas: the major cities in the State of Maryland, particularly Baltimore, have water and sewer infrastructure that is ancient, crumbling, and woefully inadequate. Every major storm causes the release of raw sewage directly into waterways. Buildings near these waterways — mostly low-income homes — suffer this raw sewage rising from toilets, bathtubs, and sinks. The sewage also spews directly into the Chesapeake Bay — the major economic, recreational, and job-producing asset of the state.

October 30, 2012 flooding, Monocacy River, Dickerson, MD. USEPA Photo by Eric Vance. Public domain image

Opponents of this tax designed to reduce run-off into the bay slapped a silly and misleading nickname onto the law in order to foment (a largely successful) taxpayer rebellion. The tax became derided as the “Rain Tax” and people were encouraged to think that they were being unfairly taxed for the uncontrollable act of nature known as rain. Although it is true that we cannot hope to control rain itself, we can all do our part to help our property to absorb rain rather than allow it to run off into storm drains. Perhaps a better name for the tax might have been the “Save the Bay” tax … or “Flood Prevention Tax” … because that is precisely what is at stake.

Source:: FloodBarrierUSA

Scientists say Hurricane Harvey was a 1000-year flood event, considered so rare we are unlikely to see anything like it for some time. However, there is a chance, albeit a small one, that the U.S. could see a storm of that magnitude again this year.

Consider other memorable storms. Hurricane Andrew, which devastated Florida and the Carolinas in 1986, was called a 100-year event. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina, another 100-year storm, flooded New Orleans. Sandy, the hurricane that famously flooded New York City in 2012, was dubbed a 700-year storm. After Harvey rolled through Houston last year, 100-year-storm Irma brought historic flooding to the Florida Keys and Gulf Coast.

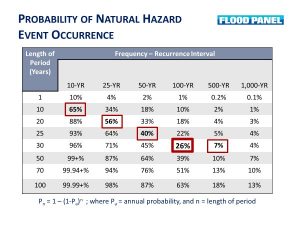

A common misconception is that these seemingly rare events can only happen once in a given period of time. Using this logic, a 1,000-year flood is an event that occurs just one time in 1,000 years. In fact, a 1000-year flood actually has a 1 in 1000 chance, or a .1 % probability, of happening in any given year.

So, should we plan for another catastrophic flood event in the U.S. this year?

The answer lies in understanding the probability of natural hazard events. According to the National Weather Service, the probability of another 500-year flood this year in Houston is .2 % or 1 in 500. NWS explains, “If a 100-year flood event occurs, that does NOT mean that people are ‘safe’ for 99 years. The risk of having the flood in any given year is the same.”

To understand probabilities for a 100-year flood, roll the dice.

If the chance of rolling a 6 is 1/6, what happens if you roll the dice six times? Does it equal a 100% chance? It is better to consider your chances of not rolling a 6, or 5/6. Instead of counting all the possibilities, simply multiply the chance that the roll will not be a 6 by the next chance it will not be a 6 and so on. Using the equation 5/6 x 5/6 x 5/6 x 5/6 x 5/6 x 5/6, you can determine the chance that you would not roll a 6. Subtract that number from 100% to determine the probability that you would roll a 6 in six attempts. The number is 66.5%, not 100%.

Using this logic for a 100-year flood, you can see that the chance that event will not happen is 99% for a given year. However, over longer periods of time, there is a greater probability for a 100-year flood (see chart.)  Houston should have been ready for Harvey. It had already endured consecutive 500-year floods in 2015 and 2016. The frequency of these so-called “rare” flood events in recent years makes a strong case to plan for events that are unlikely to happen, but can and do happen.

Houston should have been ready for Harvey. It had already endured consecutive 500-year floods in 2015 and 2016. The frequency of these so-called “rare” flood events in recent years makes a strong case to plan for events that are unlikely to happen, but can and do happen.

For information on flood mitigation planning, visit www.floodpanel.com.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently reported that last year’s storms, mudslides, wildfires and other natural disasters cost $306 billion in total damages, making 2017 the most expensive year on record.

Scientists continue to debate the role of climate change in the frequency and severity of these catastrophic events. However, “one key factor that is also known to be worsening damage is that there is more valuable infrastructure, such as homes and businesses, in harm’s way…” (https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2018/01/08/hurricanes-wildfires-made-2017-the-most-costly-u-s-disaster-year-on-record/?utm_term=.0fb11f2871ed)

Despite the known risks, coastal communities most vulnerable to a major storm remain attractive to developers and their clients eager to live and work in those areas. Many consider current flood maps to be highly inaccurate. As a result, FEMA has allowed engineers to adjust elevations using fill, levees and drainage, paving the way for new development – in some cases just two inches higher than the floodplain. In the last five years, FEMA has allowed 150,000 map changes. (https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/02/us/houston-flood-zone-hurricane-harvey.html)

The Woodlands in Texas is one of those communities. Revisions to local flood maps approved by FEMA allowed development in an area previously considered swampland. Because these structures were built above the floodplain, most homeowners were not required to hold flood insurance. FEMA statistics indicate that nearly 100 percent of homes near Spring Creek, which flows through The Woodlands, were flooded during the historic flooding caused by Hurricane Harvey. Check out our blog for a closer look at how human development made Houston storm flooding the worst in history.

Commercial businesses in flood prone coastal communities should take steps to minimize and manage the risks of flooding before disaster strikes. This can be done in two ways:

First, businesses must determine the risk of flooding and the potential losses associated with a major flood event. What is the probability of a flood? What costs will not be offset by insurance? What will it cost to rebuild if necessary?

Then National Flood Insurance Program, flood plain maps, as well as federal and local building codes and ordinances provide a lot of valuable information that can inform business owners about flood risk in their specific community. They should consider the likelihood of a flood event, from frequent, nuisance flooding to major, catastrophic events like hurricanes. Planning should also factor in events like a 500-year flood, which may seem highly unlikely, but could happen.

For more information, read our blog for specific steps contractors and business owners can take to minimize flood risk.